Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Episode Transcript:

[00:00:00] This is an episode from Twig’s Stressless Series for getting through wildfires and other natural disasters, you can find all the episodes at stressless-guide.com.

[00:00:13] Welcome to the Stressless option.

[00:00:15] I’m Anthony Wheeler. I go by “Twig”. I’m a Carlton resident and trauma specialist. I actually travel around the world talking to communities and therapists about how the stress response works and how to feel better faster after really bad stuff happens. I’m here to share some of those ideas with you and see if we can all stress a little less.

[00:00:33] I’m going to start here with a little bit of a technical conversation. This is not to be dry but to be basic for a moment. There are rules, you know, to the universe and some of them are simple and well-known. If you throw a water out of a sprinkler it’s going to go up in the air and then fall down to the ground. There are also rules to our biology, to our bodies, to our organisms, and how we function in and out of what we call the Autonomic Stress Response or “the stress response.” The awareness of those rules can help you and I to know how to help each other feel better faster.

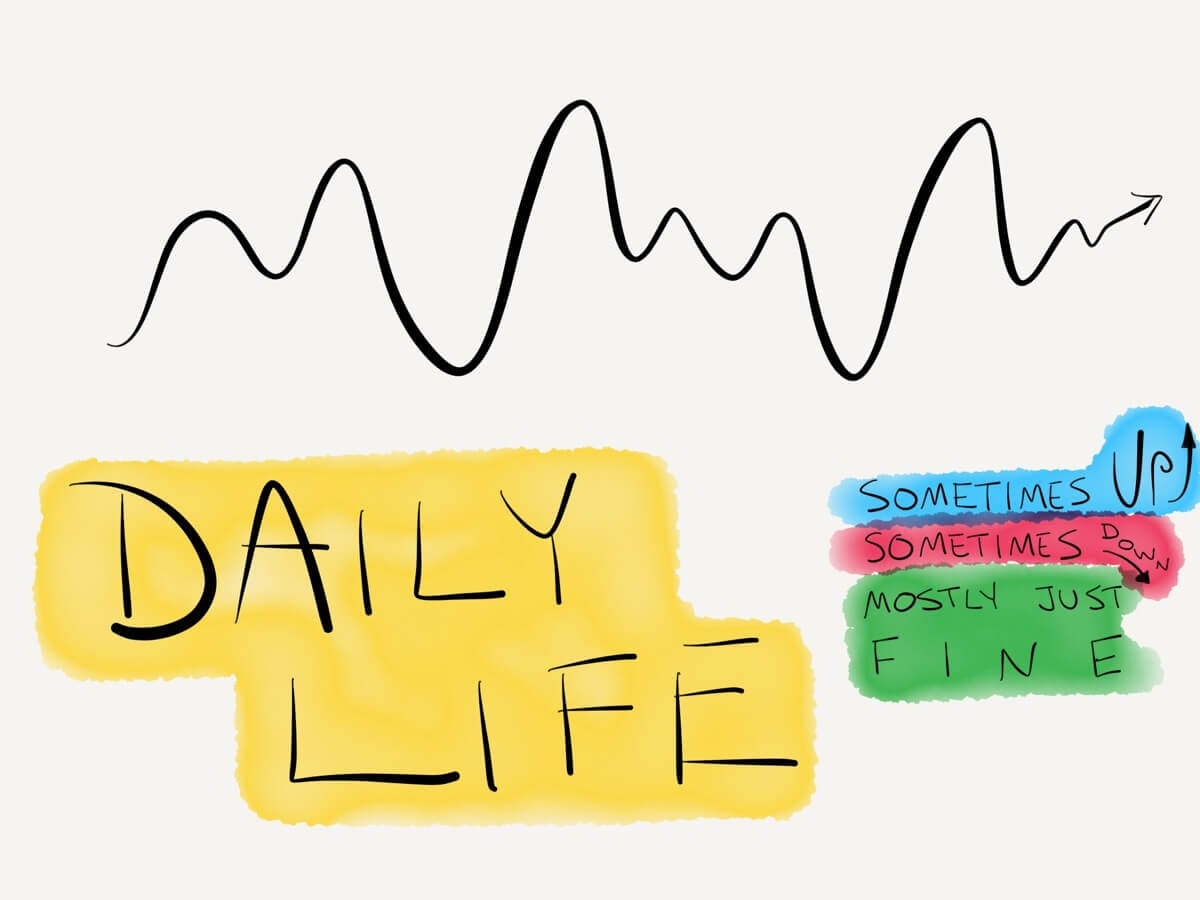

[00:01:13] Let’s name a few observations that could be made about these rules. One of them is that when we feel safe enough we have control over our behavior. If you and I are walking in the park and we’re looking at the flowers and talking about the world around us it’s all good, you know what I mean. Like we can choose which path to take. We can ramble on about this or that subject. It’s all ourselves. On the other hand if we’re out on this walk and there’s a loud sound at the other end of the park, we’re going to stop our conversation instantaneously and we’re going to turn and look in the direction of that sound. Now there’s a very basic reason that we do this and that is that if that sound happens to be dangerous to us we need to respond to it.

[00:02:01] We need to know that it’s dangerous otherwise we might get eaten. And so there is a process through which the nervous system is constantly assessing what’s in the environment, what’s going on inside of us, and putting those things together to tell us “do we feel safe enough.” And if so, the nervous system gives us freedom of our behavior and also a pretty decent feeling inside of our bodies.

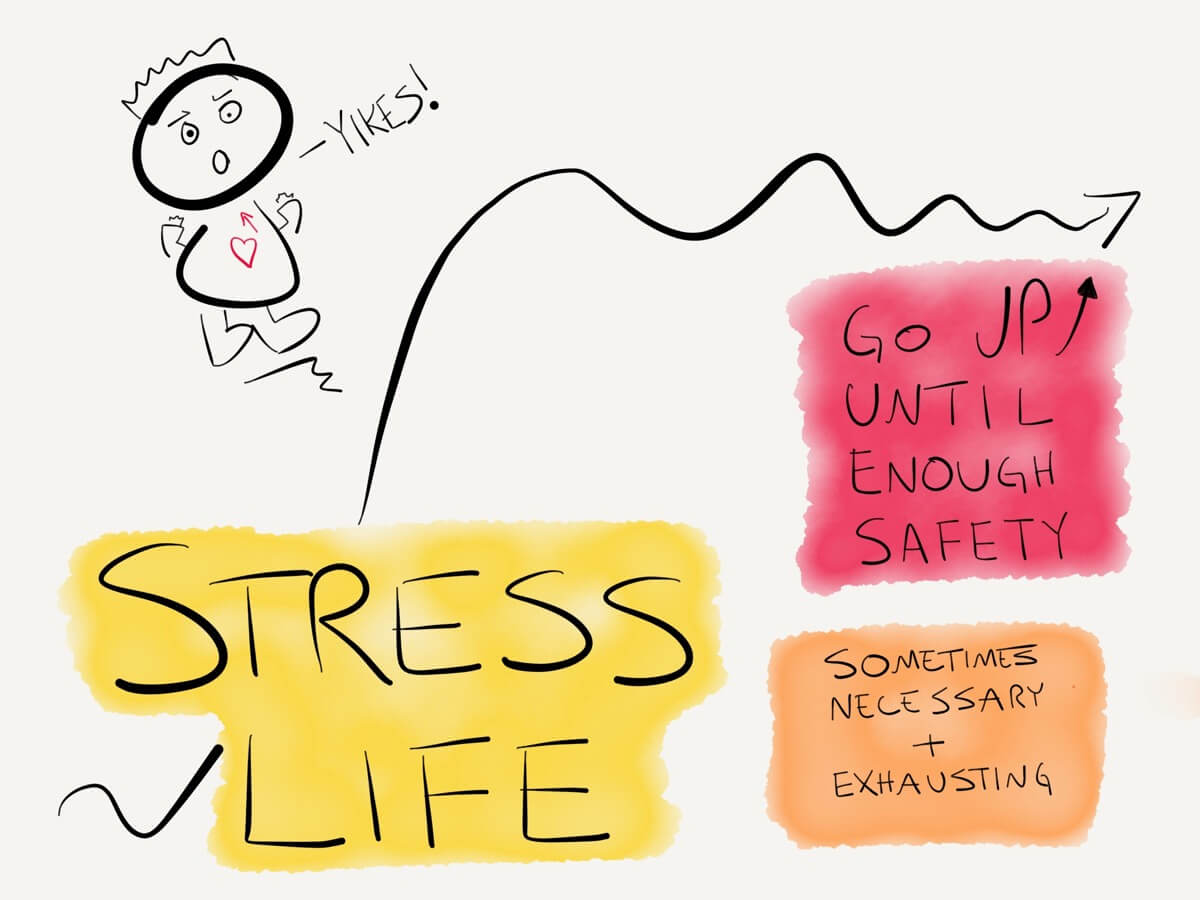

[00:02:25] However, if that assessment says you’re in danger, like “you’re falling.” Say, you just hit the corner of the sidewalk and now you’re tripping or you just dropped a heavy boulder on out of your hands and you’re jumping out of the way now or this sound is happening at the end of the park and you’re involuntarily turning your head in order to look at it and to make sure that that is not dangerous to you – all of these things are elements of the stress response coming up and taking over our behavior. Now it’s good that it does that right? If you drop that Boulder you want to be jumping out of the way before you have the thought “I dropped a boulder. I’m going to crush my foot.” You want your nervous system to be involuntarily tracking whether or not you’re safe or not. And when it notices or gets the perception that we’re in danger it’s going to then start to inform and influence what else we do. That’s a good thing.

[00:03:29] The more danger we’re in. The more the nervous system is going to control our behavior or the more involuntary our behavior will become.

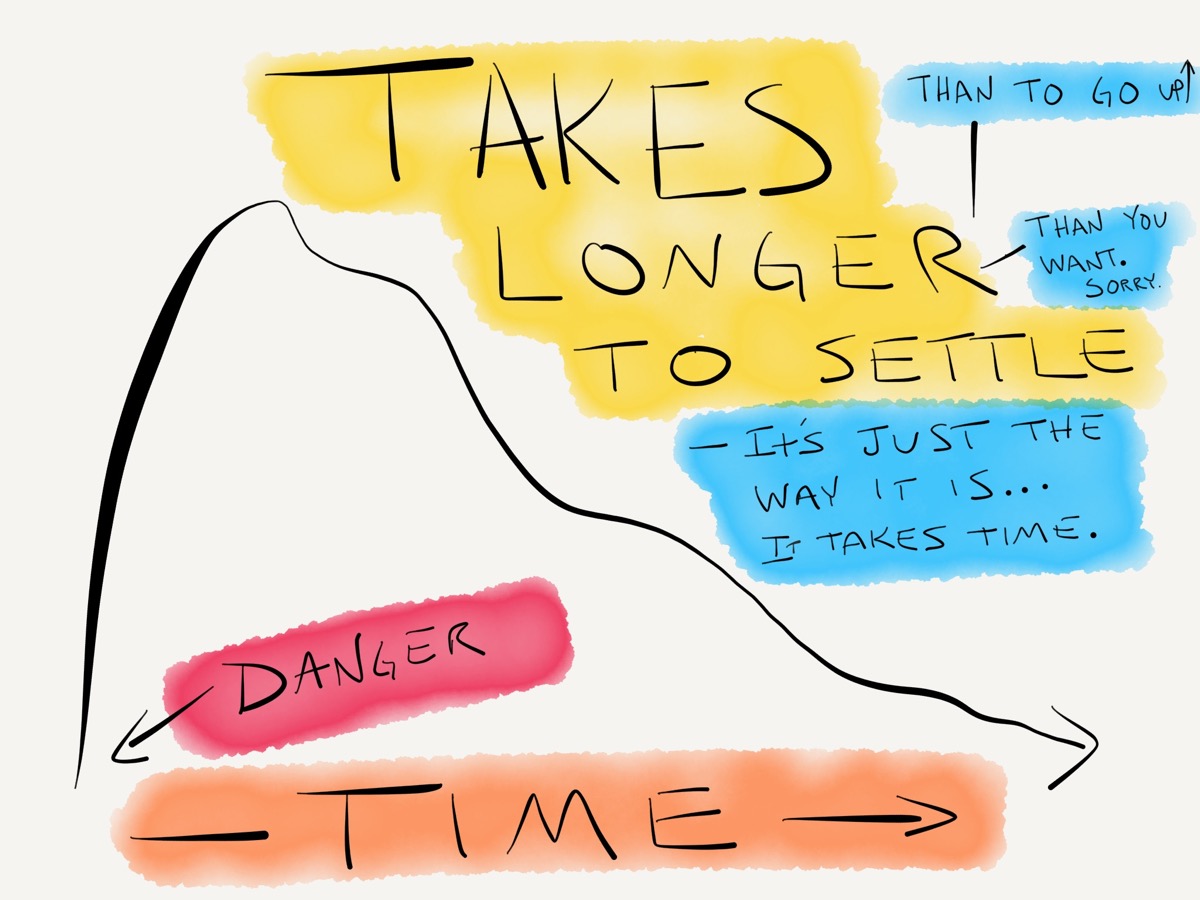

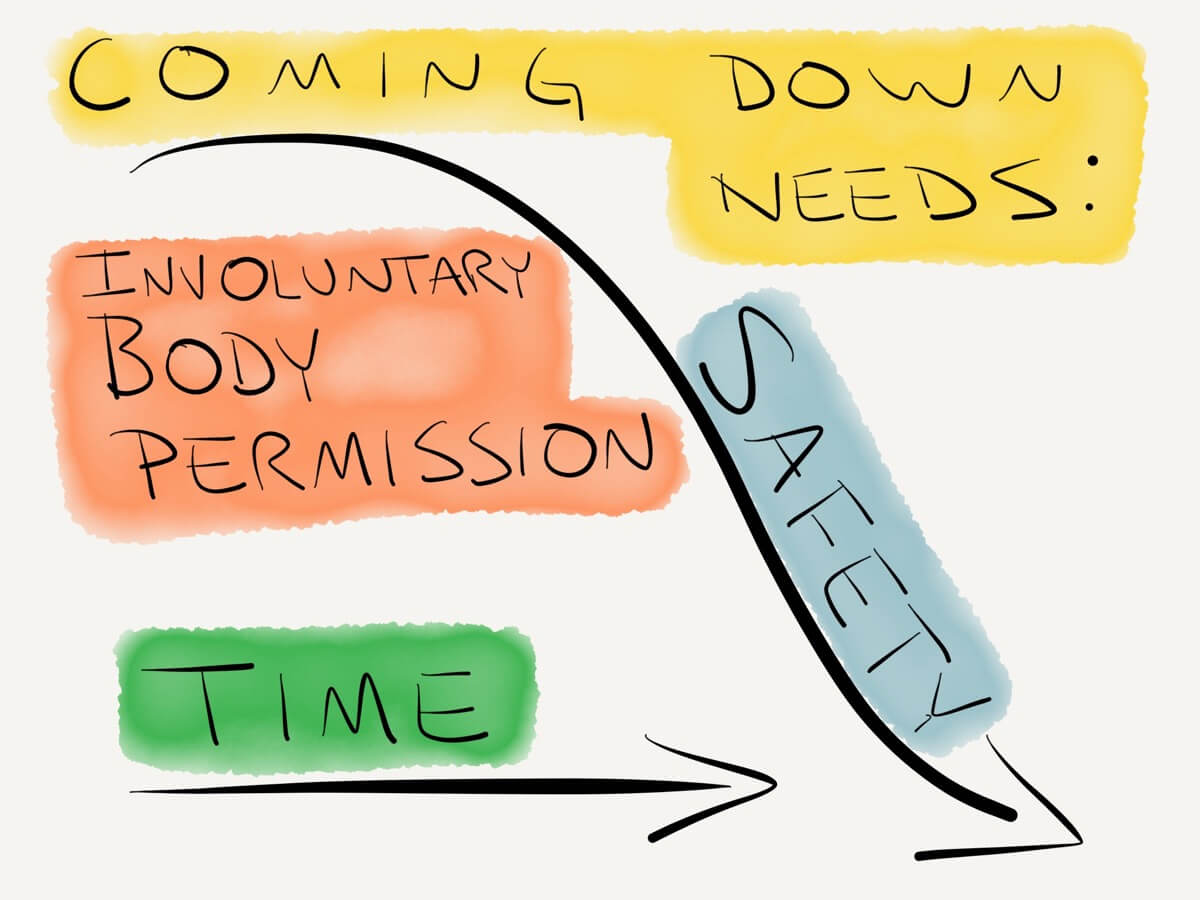

[00:03:39] Now when the stress response gets elicited when we perceive that we’re in danger it kind of runs through a stereotypical process. It’s not unlike gravity. It has a pattern of going up and then anticipates coming back down again. The idea of coming back down again is that we’re not in danger anymore so that we don’t need to maintain the stress response, which is kind of stressful to be in. And so it’s good for the body to be able to get out of the stress response just about as fast as possible.

[00:04:11] In this stereotypical pattern of a kind of rising action and a falling action we have different kinds of things that we we know about. Like you’ve heard about Fight and Flight and maybe you’ve heard about another respons called Freeze or Immobility – the animal the opossum is famous for making that one a standard knowledge, the whole playing dead thing. But everybody will do it if if a danger becomes big enough that fighting or fleeing won’t do any good we might hide or or kind of just immobilize or “freeze” in order to get through the highest intensity of the danger until something changes and then we usually come back into action of fighting or fleeing until we get back to safety again. These patterns are these plans of action. They’re all involuntary. We don’t choose to freeze and immobilize, our bodies, our nervous systems really, make that happen involuntarily – and the same with fight and flight.

[00:05:00] We don’t choose to jump away from the rock we just simply do that and it’s a good thing that we do. The nature of these reactions requires that the body mobilize certain kinds of what we can call subsystems and their related reactions, these include how our bodies are build and organized and the actions that we can take so that we can enact these kinds of survival responses like jumping away or “fleeing” from the rock or pushing it away, like “fighting back” or turning our head to look at the sound (orienting) or immobilising like the possum if necessary.

[00:05:37] All of those things come along with correlates or other things that happen at the same time when we’re fighting and fleeing. Our breath goes faster so we get more oxygen. Our heart beats faster so that it moves blood and oxygen around our bodies quicker. Our muscles in our arms and our legs get really tense so that we can run and fight.

[00:06:00] On the other hand, if we’re immobilising we get weak, we don’t feel like we can do anything, in fact we want to collapse and our heart goes really slow and our lungs go really slow, all in an attempt to conserve energy and to help our bodies to withdraw from calling attention to us if we should be under threat from a predator or from some kind of attack.

[00:06:29] All of that to say, there are things that happen in voluntarily inside the body that cost a lot in order to help us get back to safety as fast as possible when we perceive that we’re in danger. That perception is involuntary. It’s constantly happening, it’s constantly giving a reading of some kind of statement that says “I’m either safe enough or in danger.”.

[00:06:59] If that statement is “I am in danger” it’s going to control some, if not all, of our behavior.

[00:07:09] Now like gravity this pattern, this process of the stress response, is designed to go up and come down. The rock is falling, you’re jumping out of the way, the rock is now on the ground. The danger is over. You’re sitting there, you’re a little shaky, you’ve got this adrenaline coursing through you. Do you feel kind of agitated? Maybe “Up” a little bit… and now it’s starting to kind of move through and then it’s settling and you look around and you realize there are no other rocks falling, you pick up the fallen rock and you go about your business. That’s kind of a stress response writ small, like a small easy to manage, easy to experience stress response. And we do those things all the time. They protect us from falling and dropping things and and even finding popcorn when we are eating at the movies and we drop a piece and we know exactly where to go on our shirt to find it.

[00:08:08] Those are all parts of the involuntary aspect of our nervous system kind of tracking our relative danger and safety in an environment, in a situation, and it is exquisite. It’s intelligent. It does the very best it can to give us the energy we need to survive stuff that might do us harm. It’s also costly.

[00:08:35] It takes a lot of energy to run away from a bear. Fighting in a bar room brawl is just about one of the hardest things you can do. You’re kind of exhausted afterwards. Staying in the stress response longer than you need to with your heart beating fast, your lungs running fast and all the tension in your muscles going overtime, it’s a really expensive kind of thing to do for a long period of time.

[00:09:02] In fact were not designed for that. The stress response is meant to be what we call “time limited” you know that that rock is supposed to in this case fall to the ground and you jump out of the way or do some action to protect yourself. And then the danger passes and you get to settle. You get to get the signal that says “Hey, I’m not in danger anymore. There’s no more danger coming my way. I can come out of this.” And the heart the lungs all of that can quiet down.

[00:09:30] Why talk about this first? Well, one reason is to mention that the “juice” we all had when the danger first came into our valley, with these fires recently, that juice was was real. That thing that made us all drive these roads so fast and rake the ground around our houses. And do that extra effort and some of us working day and night for days on end. All of that was real and all of that was really informed by a neuroception that said we were in danger. Now we come upon a very interesting dynamic that says if we don’t pay attention to how this works, some of us – could be a good number of us – could get stuck longer in the stress response than we might need to be. And if that happens, it’s just a bummer, because it doesn’t feel good. You know it doesn’t let us rest. It doesn’t let us recover our energy. It makes us think poorly. It is intended to be more impassioned and involuntary, in a word – less intelligent.

[00:10:53] So, as much as in the moment of a real an active danger the stress response is really there on our side, for it to linger when it is not immediately necessary is a very costly kind of thing and something that will eventually wear us down. Interestingly the stress response has a pattern of “activation–deactivation” or going up and coming down and it finds its way through that all very naturally except when a danger is either so great that it really elicits that response to such an extent that you know we kind of lose ourselves completely to it or the danger lingers and we start to become conditioned toward paying attention to danger.

[00:11:44] Now the second one is a bit more of what a lot of us are going to be dealing with. That is to say that we’ve been in the stress response for a long time. A lot of the signals that we’ve been receiving from the environment around us have been reinforcing the idea, the perception that we’re actively in danger: the smell of smoke on the wind, the noise from helicopters and airplanes, the traffic in a town that doesn’t even have a stoplight in it these signals. The constant conversation of the danger that we’re having. All of those signals are active messages that say “I’m in danger – You’re in danger – I’m in danger – We’re in danger.” They all tell us we’re in danger and they all illicit, because of that, the stress response. Good. As long as we’re actively in danger. If we’re not actively endanger the cost of that signaling of the stress response is actually the cost of our health and well-being.

[00:12:47] It’s actually the cost of our ability to have calm and more mature relations with people. It’s actually the cost of our ability to think of other options and more freely because in fact the stress response is designed to have us curtail our thoughts, to have us think less and act more. What does all this say? Well one again there are rules there are kind of ways that the body is organized in order to handle stress and danger. There is also this assessment that’s being behind the scenes always taking place sane. Am I safe or am I in danger. If we’ve been in danger there is a pattern a process a plan for the nervous system to come out of that danger. If however, we don’t get the signals that would say we should come out but instead get a continuous signal that says we should stay in the stress response, we can kind of become conditioned to being in there and like with that first sound that we mentioned as attractive because it’s potentially dangerous – any further reiteration of the danger signal becomes attractive precisely because it’s dangerous and so therefore it’s easier for us to pay attention to that and consequently have our hearts racing faster, have our lungs breathing harder, have our thoughts going kind of at a higher intensity pace. Now all of those things are necessary at the right moment. All of those things are real and have been real for a lot of us and could still be real for many of us further on into the summer.

[00:14:28] However there is this need now for us to recognize are we in you me at this moment, “Am I in immediate danger?” If the answer is No. But I have been or I’ve been kind of learning or leaning toward that, if I have been in danger but I’m not in danger right now it might become necessary – and I’m going to suggest that it’s a good idea – for you to place, specifically, some of your attention in the direction of your safety so that you can start to signal to your nervous system not that you’re still in danger but instead that you’re actually more in safety now and therefore some of the process for coming out of the stress response can be signal to happen.

[00:15:15] Are you safe? No no no. I’m not saying that we’re all safe now. I’m saying that some of us, many of us, are safer or that we are safe enough to not need to concentrate solely and the danger at hand. Our environment now has a latent potential threat to it and that is going to need to continue to receive our attention. Good pay attention to that. Continue to work your fire lines, continue to water around your houses, continue to negotiate with your neighbors about helping one another out, continue to pay attention to the news.

[00:15:50] Do all of those things to protect yourself and if you notice that you’re starting to feel that it’s too much stress for too long, it could very well be that it’s necessary for you to think about: the things that you like to do the people you like to be with the places you like to go the things you enjoy doing that don’t signal danger but instead signal your relative safety so that your nervous system can get more of the signal that says I’m not actively in danger and since I’m not actively in danger I can stop or at least start to change part of the body process that happens, that goes along very naturally with the stress response.

[00:16:41] I’m going to take all of that and wrap it into one little package.

[00:16:46] There are rules to the universe. Part of those rules affects how our bodies function under stress and danger. You and I living in this valley have been under stress and danger. Our bodies have responded with that stress response intelligently to help us negotiate that danger, probably about as well as we could. Now that the danger is still present but not necessarily immediate, for us who it is not immediate, we can we have the opportunity and we might in fact have the need to specifically direct our attention towards the things that we have experienced in our lives that we have around us that help us to get a neuroception that tells us that we feel safe enough.

[00:17:40] If I were to ask you, what are you really kind of like to do in the middle of summer when you have a little bit of space from all the work that we do here in this valley. What would you enjoy doing?

[00:17:52] If you had an answer to that question. I would suggest that you try to find some time to do some of that.

[00:18:00] If you don’t have the time to do some of that, I’d suggest that you take some of the time to think about that.

[00:18:06] If you don’t have time to think about it and take five minutes to remember an image from that kind of thing that you like to do so that your nervous system, your neuroception, can get a little bit of signal that says “I’m not in that much danger right now.”.

[00:18:30] Technically speaking the stress response is designed to come out of itself. Also technically speaking, the longer it has been inside of itself repeating the signal that it’s in danger the easier it is to be attracted back to danger. Since your environment has lots of signal of danger around it, it might be necessary for us to specifically create other signals that help it to not reinforce itself quite so strongly so that once this is all over we can all feel so much better so much faster and in the meantime we can feel less stressed and frankly be able to make better decisions and enjoy our company better.

[00:19:14] That’s an option and it’s one that I’m proposing here, lean in the direction of your relative safety. For as long as you’re not in immediate danger. If you are in immediate danger let that stress response just rip, let it go let it do that thing that just makes you so amazing: “Did you know you had that much energy?”.

[00:19:36] And once it’s no longer necessary, look around for the things that tell you you’re safer: your people, your friends, your valley, the things that have been good for you. Take a look back at them so that your nervous system can get a little bit a sense that it’s not under so much threat.

[00:19:56] That’s a technical start. The autonomic stress response. It’s got a pattern. It’s got a plan. It does stuff you don’t want to get stuck there. I don’t want to get stuck there. We do not want to get stuck there. So let’s help ourselves get out. Look towards safety. If you got it go in that direction.